This chapter describes the economic and indirect effects that would occur with implementation of the NEC FUTURE Tier 1 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (Tier 1 Draft EIS) No Action and Action Alternatives.

This chapter is organized as follows:

While transportation investment alone does not generate economic activity, it can influence the pace and location of economic growth when other factors such as available skilled labor, competitive business costs, and other regional competitive advantages are favorable. A transportation system supports a region's economic activity to the degree that it 1) has sufficient capacity to meet demand; 2) offers connections to markets where travelers want to visit; 3) provides a range of prices and travel times that serve a variety of markets; and 4) offers reliable and safe options. Conversely, congestion, unreliable travel times, comparatively high travel costs (in time or fares), and the inability to readily connect and access locations within the region hinder economic activity and impose a penalty on an area's economic potential.

Beyond the transportation system's potential impact on the operation of an urban economy, the frequency, reliability, pattern, and accessibility of transportation influences how urban economies compete or cooperate in the larger national and global economy. Urban economies such as those that regularly dot the Northeast Corridor (NEC) are part of a larger interdependent cluster of cities, towns, and developed areas. Changes in the connections and interdependencies within the urban system-viewed regionally, nationally, or even globally-influence economic prospects and growth. Changes in transportation cost, connectivity, and mobility directly influence the connections among urban economies and can alter these relationships-allowing a place to become a hub or focal point for commerce, or conversely, making a place more peripheral to the region's commercial center. Changes in these interdependencies influence urban growth along the corridor thereby increasing the potential for indirect effects to occur within the region.

The Northeast Regional Economy in the Context of the National Economy

The Northeast regional economy, which approximates the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, is unique among U.S. regional economies in that it is the most densely urban 1 region in the United States, with the NEC connecting some of the nation's largest and most mature urban economies. The region has the following distinct characteristics that shape its outlook for future growth:

Within the region, the economic fortunes of individual economies are linked through commuting patterns (bedroom community and job center), connections between the nation's financial and government centers, and connections among knowledge-based industries that benefit from frequent in-person collaboration. One example is the bio-tech, medicine, and pharmaceutical industrial cluster. The region hosts numerous major research universities and national laboratories (e.g., the National Institutes of Medicine and Health), and leading bio-tech and pharmaceutical firms in Boston, Wilmington, DE, and New York City.

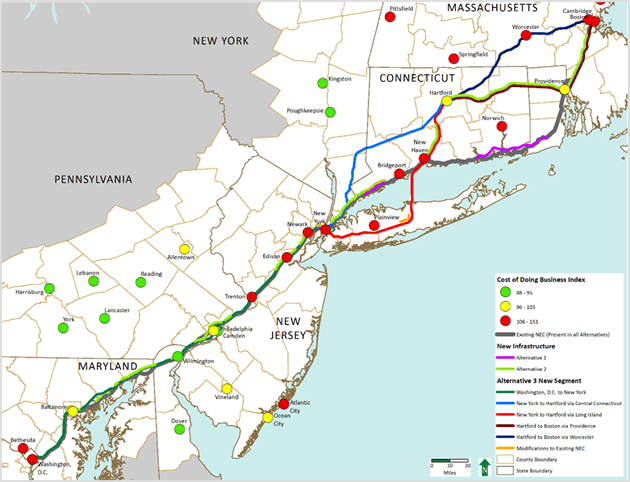

Figure 6-1: Cost of Doing Business Index (2009) along the Action Alternatives

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: Total Business Costs Index, U.S. Average = 100

The degree to which the regional economies within the NEC are fragmented or functioning in a complementary way influences how urban areas within the NEC compete against urban economies in the rest of the United States. On a global scale, the interconnected cities along the NEC are competing with established and emerging global centers of commerce for access to labor, knowledge, capital, and quality of life.

The region's infrastructure has some of the oldest assets in the nation's transportation network. To maintain its role as a global economic center, the region must modernize its aging infrastructure and add capacity to support future growth. Absent the ability to efficiently move large numbers of people in, out, and between these large economic centers daily, the negatives of large metropolitan economies begin to cancel the positives, tempering economic development and incentivizing businesses to expand elsewhere in the United States. Moreover, investments to aid in this circulation must be able to channel the flow of travelers around the region's dense stock of development that is already in place.

This assessment considers the economic effects of the Tier 1 Draft EIS Action Alternatives that result from the following:

This section presents an overview of the methodology used for the economic effects and indirect effects assessments. (Appendix D contains the full methodologies.) The assessment evaluates the potential for each of the Action Alternatives to result in economic and indirect effects within a defined Affected Environment, which is equivalent to the NEC FUTURE Study Area.

The Action Alternatives may each generate near-term economic effects during the construction period and initial periods of operation. Longer-term economic effects may include market response to improved and new rail services. Those economic effects associated with construction would be realized over the construction period and for the purposes of this Tier 1 Draft EIS the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) assumed construction would be completed by 2040. The assessment for all other types of economic effects focuses on full build-out conditions reached in 2040.

The FRA evaluated the following near-term economic effects for the Affected Environment as a whole:

The FRA will include potential economic effects driven by changes in travel time, reliability, cost, safety, and emissions and possibly additional rail capacity in the Benefit-Cost Analysis and incorporate them in the Service Development Plan.

The FRA evaluated the following longer-term economic effects within the Affected Environment at the metropolitan or station level:

In addition, this assessment considers the potential indirect effects of the Action Alternatives. The FRA assessed potential indirect effects on resource topics presented in the Tier 1 Draft EIS that could occur in metropolitan areas served by the Action Alternatives based on the potential for each Action Alternative to result in program-related induced growth. The FRA evaluated the potential for program-related induced growth based on how each Action Alternative performs with respect to identified factors:

The indirect effects assessment presents the potential for indirect effects to occur by Action Alternative and highlights areas of particular sensitivity for further consideration during Tier 2 analysis.

The construction and operation of the rail improvements and services in the No Action and Action Alternatives would result in changes to economic activity throughout the Study Area. Some changes would be immediate, while others would take place over a longer period. These economic effects include Economic Development Response, Travel Market Effects, Construction and Rail Sector Employment Effects, and Indirect Effects associated with potential economic growth, as summarized below.

Economic Development Response

The Action Alternatives accommodate greater numbers of rail travelers and allow these travelers to make their trips faster and to a greater variety of destinations within and between the urban economies that line the corridor. The expansion of regional travel choices would allow households to access a greater range of employment and leisure options via rail from their home location-thereby improving quality of life. Businesses gain access to a larger, more diverse, and specialized pool of labor-thereby increasing productivity. The Action Alternatives would also accommodate a greater flow of people between major commercial centers and metropolitan areas.

Travel Market Effects

Changes in mobility and connectivity proposed for each Action Alternative can be monetized to estimate the economic effects of transportation improvements as a function of travel time and cost savings as well as other factors such as safety and air quality impacts. The Action Alternatives offer faster travel times for many existing rail-served markets, expand service to markets not currently served, and offer a greater range of pricing.

Construction and Rail Sector Employment Effects

Indirect Effects

The FRA estimated the economic effects of the Action Alternatives for each stage of project implementation. First, the Action Alternative is built, generating construction effects discussed in Section 6.3.2. Once constructed, the Action Alternative begins service, supporting employment through its operation and travel user benefits through its use. For example, travel user benefits include travel time, travel cost, and safety benefits. Section 6.3.3 and 6.3.4 discuss these effects. Finally, once the Action Alternative is in use, the market responds to the availability of this new service. Section 6.3.5 describes the market response. Section 6.3.6 describes potential indirect effects that could result from induced growth.

The construction of the Action Alternatives would influence economic activity along the NEC. Building the requisite rail facilities would expand payrolls for the duration of the construction cycle. As noted in the Construction and Rail Sector Employment section of the Economic Effects Summary (Section 6.2), potential construction effects occur primarily within the Affected Environment and represent a large, one-time stimulus to the economy. Construction jobs (measured as job-years) range from approximately 300,000 under the No Action Alternative to a high of 3.5 million for Alternative 3 (average of Alternative 3), rising with the level of capital investment required to build each Alternative.

Construction effects estimates are expenditure driven-the larger the capital investment, the larger the construction activity and level of employment. Thus, the pattern of relative jobs and earnings across the Action Alternatives follows the pattern of costs.

The construction hiring associated with the Action Alternatives represents the direct effects of investment in the NEC. The earnings of these newly hired construction workers would translate into a proportional increase in consumer demand as these workers purchase goods and services in the region. As employers hire to meet this increase in local consumer demand and to provide materials and supplies for the Action Alternatives, a further increase of new employment across a variety of industrial sectors and occupational categories is expected. This latter hiring represents some of the Action Alternatives' potential indirect and induced impact.

This analysis focuses on the net effects generated by new investment in the regional economy resulting from the Action Alternatives and based on capital cost estimates developed for each of the Action Alternatives. (See Appendix B.6, Capital Costs Technical Memorandum.)

The analysis includes construction effects for the following:

The capital expenditures for construction of the Action Alternatives are estimated to cost between $63.6 billion and $307.9 billion (in 2014 dollars), depending on the Action Alternative, as discussed in Chapter 4 of this Tier 1 Draft EIS. There are four main categories of capital expenditures:

The potential economic impact of these capital expenditures would vary significantly by activity and depend on the amount of regionally produced goods and services embodied in the purchase.

Construction of the Action Alternatives represents significant capital investment in the local economies within the Affected Environment. This spending would increase employment for the duration of the construction process. This section describes the potential direct and total employment impacts.4

The employment effects of the No Action and Action Alternatives are expressed in job-years, which is defined as one full-time job for one person for one year. For example, three job-years are equal to three people doing a job for one year, or one person doing a job for three years.

In order to isolate the potential economic effects of each of the alternatives within the Affected Environment, an economic impact analysis typically distinguishes between resources that are new to the economy and that would not be invested in counties within the Affected Environment but for the Action Alternatives from resources that would still be spent in the region with similar economic effects (e.g., funds that would be allocated to other transportation construction projects in the region). The analysis makes this distinction because only potential impacts from new funding sources would support employment in the Affected Environment that would not otherwise occur. At this stage of planning, the funding sources are not known. Thus, in the absence of information on how funds would be secured, the FRA applied the full cost of the Action Alternatives and assumed that the rolling stock is constructed in the United States but not necessarily in the Affected Environment.

The effect of capital spending for Alternative 1, for example, would result in nearly 809,900 job-years, of which approximately 384,600 are direct job-years, assuming that the rolling stock is manufactured in the United States, but outside of the Affected Environment.

Construction would result in an average of nearly 40,500 total jobs per year.5 Compared to the typical Walmart with 250 employees, construction of Alternative 1 is like hiring employees for 162 new Walmart locations within the Affected Environment every year.6 Table 6-1 shows the results for the No Action and Action Alternatives. The employment impacts for the four Alternative 3 route options are similar, so ranges are shown in the table.

Construction of any of the Action Alternatives represents significant capital investment in the local economies of the NEC region. This spending would increase earnings for the duration of the construction process. This section describes the potential total earnings impacts.

The effect of capital spending for Alternative 1, for example, would result in up to $39,240 million in earnings (2014 dollars),7 assuming that the rolling stock is manufactured in the United States, but outside of the Affected Environment. This would result in average earnings of about $48,500 per job-year, assuming the rolling stock is manufactured outside of the Affected Environment but inside the United States.8

To put these results into context, the No Action Alternative would result in average earnings of about $47,400 per job-year.9 Table 6-2 shows the results for the No Action and Action Alternatives. The earnings impacts for the four Alternative 3 route options are similar, so ranges are shown in the table. While the average wage reported above is low for many building trades, it reflects an average wage across the direct construction jobs and jobs supported across a variety of industries as construction workers spend their wages for goods and services and materials and supplies are purchased.

The building activity needed to construct the No Action Alternative and each of the Action Alternatives represents the most-immediate economic outcome associated with implementation. These are large economic effects that last for the duration of the construction cycle only. The estimates of construction effects are expenditure driven-the larger the investment, the larger the construction effect. Thus, the pattern of relative jobs and earnings across the Action Alternatives follows the pattern of costs.

| No Action Alternative Total |

Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | ||

| Direct Employment (in Job-Years) | 147,300 | 377,200 | 7,410 | 761,000 | 15,800 | 1,543,600-1,823,000 | 16,600 |

| Total Employment (in Job-Years) | 297,800 | 773,670 | 36,200 | 1,561,100 | 77,400 | 3,166,500-3,739,900 | 81,000 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

| In millions of $2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Action Alternative | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |||

| Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | Affected Environment | U.S.-Outside Affected Environment | |

| $14,120 | $37,530 | $1,710 | $75,750 | $3,650 | $153,660-$181,495 | $3,815 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

Unlike the construction effects that represent a one-time stimulus to the economy, employment and earnings effects associated with an Action Alternative's O&M are recurring impacts that would last for the duration of the system's operation. As highlighted in the Construction and Rail Sector Employment Effects portion of Section 6.2, additional hiring would be required to operate and maintain the expanded rail service; the amount of employment supported rises incrementally across the No Action (lowest at 3,100 job-years) and Action Alternatives. Alternative 3 offers the greatest expansion and accordingly supports the greatest employment gain (29,200 job-years). Operating and maintaining the rail service proposed for each Action Alternative would expand payrolls in each year of operation. The O&M hiring associated with the Action Alternatives represents the direct effects within the Affected Environment. The earnings of these newly hired rail sector employees would translate into a proportional increase in consumer demand as these workers purchase goods and services in the region. Purchases of materials and supplies to support operations would further support jobs and earnings. A further increase of new employment across a variety of industrial sectors and occupational categories would occur as employers hire to meet this increase in demand. This latter hiring represents some of the Action Alternative's potential indirect and induced impact.

Although implementation of an Action Alternative would be incremental and phased over time, this assessment assumes additional employment and earnings in the rail sector (in 2014 dollars) for the fully implemented Action Alternative in the horizon year of 2040. The Action Alternatives comprise two service types: Intercity-Express and Intercity-Corridor. This chapter presents the rail-sector employment and earnings estimates for the two service types for the Affected Environment as a whole. Though not estimated for this analysis, there is likely to be an increase in employment in the commuter rail sector, which can have multiplier effects within the Affected Environment in addition to the effects measured in this analysis.

The results shown focus only on the potential additional incremental economic impacts attributable to the Action Alternative (i.e., the marginal difference between future conditions assuming existing rail service levels and the future conditions under implementation of each Action Alternative) in 2040.

Jobs supported through expenditures for rail operations and maintenance are recurring jobs; they are anticipated to remain as long as the service is operated. The following section describes the potential direct and total employment impacts from O&M of the Action Alternatives.

On a yearly basis, operation of each Action Alternative is equivalent to hiring for:*

*Calculated by dividing Total Employment from Table 6-3 by 250 employees in a typical Walmart

The employment effects are expressed in job-years, or one job for one person for one year. If one person held the same job for three years, this would be equivalent to three job-years. For this analysis, the FRA assumed that funding for O&M would be procured from federal and local government funds as well as project-generated funds such as ticket revenues and food and beverage purchases. Although some of these expenses would originate from local sources, this represents spending that would not take place but for the implementation of the Action Alternative service along the NEC. The expansion of rail passenger service associated with these Action Alternatives represents an expansion of economic activity within the Affected Environment and thus generates potential recurring net economic impacts (long-term).

The analysis considers the change in direct and total employment as compared to the existing service. Because O&M costs are defined by the two service types (Intercity-Express and Intercity-Corridor), the employment may be higher or lower than the existing service, resulting in positive potential impacts when there is greater service anticipated than existing, or negative potential impacts when less service is anticipated than existing.

The O&M costs for the Action Alternatives assume existing Intercity fares similar to today, as adjusted to normalize the premium placed on travel through New York City and to balance ridership, revenue, and cost. (Refer to Appendix B.9, Operations and Maintenance (O&M) Costs Technical Memorandum for more information.)

Table 6-3 shows the results for the No Action and Action Alternatives. The employment impacts for the four Alternative 3 route options are similar, so ranges are shown in the table.

The pattern of earnings across the Action Alternatives follows that for operating and maintenance employment, and the general framework under which the estimates are made is also the same. Briefly, the annual O&M of the Action Alternatives would increase employee earnings in the region as long as the service is operated. These potential impacts are long-term annual impacts that would continue for the life of the service. This section describes the potential anticipated earnings impacts from the Action Alternatives. Table 6-4 summarizes the results for each Action Alternative, expressed in millions of 2014 dollars. In order to estimate the potential earnings impacts that result from employment for the full build-out, the analysis converted O&M expenses from 2013 dollars to 2014 dollars using GDP Chained Price Index deflators.10

The analysis considers the change in total earnings as compared to the existing service. Because O&M costs are defined by the two service types, the earnings may be higher or lower than the existing service, resulting in positive potential impacts when there is greater service anticipated than existing, or negative potential impacts when less service is anticipated than existing.

The effect of O&M spending for Alternative 1, for example, would result in a total of $379 million in earnings in 2040.

| Service Type | No Action Alternative | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Employment (Job-Years) | Total Employment (Job-Years) | Direct Employment (Job-Years) | Total Employment (Job-Years) | Direct Employment (Job-Years) | Total Employment (Job-Years) | Direct Employment (Job-Years) | Total Employment (Job-Years) | |

| Intercity-Express | 1,000 | 1,300 | 300 | 500 | 3,100 | 4,300 | 5,700-6,600 | 8,000-9,200 |

| Intercity-Corridor | 1,300 | 1,800 | 8,000 | 11,000 | 12,500 | 17,300 | 14,400-15,800 | 20,000-21,900 |

| TOTAL | 2,300 | 3,100 | 8,300 | 11,500 | 15,600 | 21,600 | 20,100-22,400 | 28,000-31,100 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

| Net of existing service, in millions of $2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Type | No Action Alternative | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* |

| Intercity-Express | $43 | $17 | $146 | $271-$311 |

| Intercity-Corridor | $57 | $361 | $570 | $662-$721 |

| TOTAL | $100 | $379 | $716 | $933-$1,032 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: For the Action Alternatives, counts shown are the change from No Action Alternative.

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

Table 6-4 shows the results for the No Action and Action Alternatives. The earnings impacts for the four Alternative 3 route options are similar, so ranges are shown in the table.

Even with its large existing rail transportation network, the NEC corridor is capacity constrained under the No Action and this tempers potential economic growth. One of the most important findings of the NEC analysis is that there is currently unmet demand for rail travel in the corridor. The demand for transportation is derived demand because the large majority of travel is not for the purposes of the transportation itself, but as a means to reach a destination. When travelers are unable to make trips in their preferred manner and must select the second-best option, this imposes a cost on the consumers' or businesses' economic choice. When large numbers of travelers must repeatedly select their second-best option or when there are capacity constraints on urban economies' abilities to reliably move large numbers of workers in and around the economy, the growth potential of this already high-cost corridor (see Section 6.1) is tempered.

Although Alternative 1 offers greater capacity over the No Action Alternative, neither fully meets demand for rail service. By contrast, Alternatives 2 and 3 fully meet demand. Only Alternative 3 provides capacity for rail market growth beyond the analysis period.

The tightest constraint in the corridor is at the Hudson River where 6,600 more passengers want to travel by rail per hour than can be accommodated under the No Action Alternative. Alternative 1 offers an improvement over the No Action Alternative but would remain constrained with demand for rail service exceeding available seats by roughly 2,900 passengers per hour. Alternatives 2 and 3 fully address the capacity constraints present in the No Action Alternative and would accommodate projected demand. In short, Alternative 1 provides an incremental reduction in the cost penalty for the region, while Alternatives 2 and 3 completely remove this burden on the region's economy.

In concert with the reduction or complete removal of the rail service capacity constraint, the Action Alternatives offer faster travel times for many existing rail-served markets, expand service to markets not currently served, and offer a greater range of pricing. Collectively, as highlighted in the Travel Market Effects portion of Section 6.2, these changes allow travelers to make different travel choices than under the No Action Alternative. This change in travel behavior is important because transportation investment influences economic outcomes when and only it first solves a transportation challenge or fills a gap in the market. This section describes the economic value of changes in travel behavior in terms of time saved, travel costs avoided, greater safety through the avoidance of crashes, and the avoidance of emissions. The following section, Section 6.3.5, qualitatively describes the characteristics of the Action Alternatives that would influence the character and location of economic development as the rail travel market achieves a higher level of performance.

Transportation investment by itself cannot cause economic development beyond supporting construction activity. To influence long-term economic outcomes, the transportation investment must allow travelers to make better choices and companies to access different or expanded markets. These changes in traveler behavior and market access, in turn, spark economic development.

One of the key changes in travel behavior observed is that when offered a greater range of travel options, travelers selected slower modes of travel in order to save money. Thus, some existing rail travelers shifted from faster trains to slower less expensive rail options and some air travelers diverted to rail. Bus travelers, by contrast, were willing to pay a higher fare for the greater comfort offered by rail when a wider range of frequencies and fare options were available to them. Auto travelers saw that largest benefits, gaining both time and cost savings by shifting to rail.

For existing rail travelers, Alternative 1 offers the greatest improvement in combined travel time and travel cost savings. Alternatives 2 and 3 also offer savings but the magnitude is less than for Alternative 1. By contrast, for all other travelers who divert to rail (air, bus, and auto) the estimated savings rise across the alternatives with Alternative 1 offering the smallest gains in combined travel time and cost savings and Alternative 3 offering the greatest gains. Travel cost savings represent real gains in disposable income that supports economic activity in the region.

The balance of this Travel Market Effects section describes the benefits to rail travelers in terms of reduced travel time, travel cost, and the reduced likelihood of crashes. All residents of the corridor-whether a rail traveler or not-would benefit from reduced emissions. The effects associated with the Action Alternatives are expressed as net benefits or costs, with positive values showing benefits within the Affected Environment and negative values showing costs within the Affected Environment, between the 2040 No Action and Action Alternatives. All values are reported in 2014 dollars. In addition to monetized changes in travel time, travel costs, safety incidents, and emissions, estimates of capacity changes for the network, the potential for passenger-freight conflicts are qualitatively described.

Travelers weigh a variety of attributes when making travel choices. While it may seem counter-intuitive, passengers may shift from air to rail under an Action Alternative because they find it more convenient due to increased frequencies, time of day travel needs, and spacious seating. Easy access from rail stations to downtowns, absence of screening, and availability of free wireless internet and power plugs may ease the experience and make rail travel more productive than air.

While the value of travel time savings and cost savings are described in greater detail later in this section, Table 6-5 displays the net change in the value of travel time and travel cost savings for diverted users by mode, and shows the trade-off that some travelers make for travel costs and time. For example, air travelers who shift to rail predictably pay a penalty (or loss) in travel time-ranging between $77 million for Alternative 1 and $105 million for Alternative 3. They more than make up this loss, however, in travel cost savings. When both the value of travel time and travel cost are considered jointly, the net benefit for air travelers diverting to rail ranges from an estimated $75 million under Alternative 1 to an estimated $104 million under Alternative 3. Table 6-5 illustrates similar travel time and travel cost tradeoffs for each mode and alternative. These travel cost savings represent real gains in disposable income that is available for other types of expenditures or saving.

| In millions of $2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | ||

| Travelers Shifting from Air to Rail | Change in value of travel time | -$77 | -$95 | -$105 |

| Change in travel cost | $152 | $187 | $209 | |

| Net change | $75 | $92 | $104 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Auto to Rail | Change in value of travel time | $354 | $437 | $560 |

| Change in travel cost | $592 | $668 | $705 | |

| Net change | $946 | $1,105 | $1,265 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Bus to Rail | Change in value of travel time | $100 | $127 | $152 |

| Change in travel cost | -$48 | -$72 | -$90 | |

| Net change | $52 | $55 | $62 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Rail to Rail** | Change in value of travel time | -$3 | -$72 | -$37 |

| Change in travel cost | $470 | $407 | $367 | |

| Net change | $467 | $335 | $330 | |

| Alternative 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Connecticut/ Providence (3.1) | Long Island/ Providence (3.2) | Long Island/ Worcester (3.3) | Central Connecticut/ Worcester (3.4) | ||

| Travelers Shifting from Air to Rail | Change in value of travel time | -$134 | -$74 | -$139 | -$74 |

| Change in travel cost | $210 | $205 | $215 | $207 | |

| Net change | $76 | $131 | $76 | $133 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Auto to Rail | Change in value of travel time | $458 | $663 | $458 | $661 |

| Change in travel cost | $697 | $686 | $719 | $717 | |

| Net change | $1,155 | $1,349 | $1,177 | $1,378 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Bus to Rail | Change in value of travel time | $135 | $167 | $140 | $165 |

| Change in travel cost | -$88 | -$89 | -$95 | -$88 | |

| Net change | $47 | $78 | $45 | $77 | |

| Travelers Shifting from Rail to Rail** | Change in value of travel time | $6 | -$64 | -$3 | -$85 |

| Change in travel cost | $331 | $349 | $383 | $404 | |

| Net change | $337 | $285 | $380 | $319 | |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: Positive values indicate a benefit to users while negative values indicate a cost.

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

** Rail excludes base passengers.

This section describes the travel time benefits associated with the Action Alternatives for Intercity and Regional rail services.

Intercity Rail Travel Time Savings

Improvements to Intercity rail capacity and service would result in travel time savings for Intercity rail users, which can be broken down into three components:

The FRA calculated changes in travel times for Intercity rail service within the Affected Area by metropolitan area and summed. To derive the travel time savings, the FRA compared Travel Demand Model outputs associated with each Action Alternative with the No Action Alternative model outputs, for year 2040, for the 14 metropolitan areas. The FRA measured travel times (of what), including in-vehicle and out-of-vehicle time in minutes. For base Intercity rail trips, the FRA calculated the total time savings associated with each of the Action Alternatives by multiplying the number of base trips with the change in travel times between the No Action and Action Alternatives, and then summed at the metropolitan area level. For trips diverted from other modes of transport and between the Intercity rail services, the FRA calculated the total time savings by multiplying the number of trips diverted from each mode/service by the change in travel times between the two modes/service for each zone pair, and then summed at the metropolitan area level. The FRA converted annual minutes to hours and multiplied by the value of time for business and personal travel. Comparing the No Action Alternative to the annual travel time savings for auto, air, bus, and rail users diverting to Intercity passenger rail results in the net change in travel times for each Action Alternative. Positive values for change in travel times indicate travel time savings, while negative values indicate that travelers would not save time by using Intercity passenger rail.

Due to improved Intercity rail capacity and service, people traveling by auto, bus, rail, and air in the region may divert to Intercity passenger rail in the Action Alternatives, which would lead to greater connectivity. Passenger rail users may experience some travel time savings.

The FRA derived the Intercity value of travel time benefits for year 2040 by applying the values of time for personal and business trips to the 2040 travel time savings by Action Alternative, mode, and metropolitan area for diversions to Intercity passenger rail. Table 6-6 shows the 2040 value of travel time savings associated with the Action Alternatives as compared to the No Action Alternative.

| In millions of $2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Air | ($77) | ($95) | ($105) |

| Auto | $354 | $437 | $560 |

| Bus | $100 | $127 | $152 |

| Rail | $1,597 | $1,472 | $1,500 |

| TOTAL | $1,973 | $1,941 | $2,106 |

| Alternative 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Connecticut / Providence (3.1) | Long Island / Providence (3.2) | Long Island / Worcester (3.3) | Central Connecticut / Worcester (3.4) | |

| Air | ($134) | ($74) | ($139) | ($74) |

| Auto | $458 | $663 | $458 | $661 |

| Bus | $135 | $167 | $140 | $165 |

| Rail | $1,743 | $1,306 | $1,728 | $1,222 |

| TOTAL | $2,202 | $2,062 | $2,186 | $1,974 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: Rail includes travel time savings for base and diverted riders.

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

The mix of diversions to and from modes may result in positive time savings for users who divert from slower modes to faster modes, or negative time savings (with cost savings) for users diverting from faster modes to slower modes. As shown, the travel time savings for air are negative across the Action Alternatives, indicating it would take longer to use Intercity-Corridor service than air. Rail users would divert between Intercity-Express and Intercity-Corridor modes; though passengers who divert from Intercity-Express to Intercity-Corridor services lose time, the overall time savings would be positive for all Action Alternatives because of the time savings experienced by base passengers using Intercity rail and passengers diverting from autos.

There may be a number of reasons why riders choose to divert from Intercity-Express and air to Intercity-Corridor services, which results in the negative travel time savings. The Intercity-Corridor fare is lower than the other two modes, and although the travel time is longer, there are other factors contributing to the decisions to divert. Passengers may find Intercity-Corridor service to be more convenient due to the increased frequencies, time of day travel needs, more spacious seats than on an airplane, the availability of wireless internet and power plugs may make travel time more productive than air, and easier access from rail stations to downtowns than airports. The more frequent and affordable Intercity-Corridor service results in diversions from Intercity-Express rail and air.

Regional Rail User Benefits

By contrast to the value of Intercity passenger rail savings (presented in Table 6-6), the FRA does not monetize Regional travel time savings for this Tier 1 Draft EIS with the same methodology. The reason is that the primary savings for regional travelers is in reduced wait times, and the travel time savings are estimated instead by a metric called User Benefits. Since all Action Alternatives allow the NEC to operate reliably, the magnitude of the benefit to Regional travelers would vary with the degree to which Regional trains operate on the NEC. (Many Regional trains begin an inbound trip off the NEC and only operate on the NEC for a portion of the total trip.) The FRA estimated User Benefits of Regional rail according to Federal Transit Administration guidance, and are a measure of both travel time and travel cost savings. User Benefits are a proxy measure, representing travel utility as the difference in user costs between alternatives. It includes prices in terms of out-of-pocket costs and the cost of time. As a result, User Benefits are valued approximately as travel time savings in total annual hours. The FRA measured User Benefits for base Regional rail riders as well as Regional rail diversions from transit and autos. The FRA applied the value of time for local travel, all purposes of $13.20 per hour11 for all geographies and all Action Alternatives, relative to the No Action Alternative.

Table 6-7 shows the millions of hours of User Benefits in the metropolitan areas that result from diversions to Regional rail service. The millions of annual auto diversions are shown for the Action Alternatives compared to the No Action Alternative, with Alternative 3 representing all Alternative 3 route options.

| Net of No Action Alternative, in millions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Annual Hours of User Benefits (Travel Time Savings) | 47 | 72 | 94 |

| Annual Auto Diversions | 36 | 42 | 74 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

As shown in Table 6-7, the auto diversions contribute a relatively low percentage of User Benefits. As a result, Regional rail customers would realize most of the User Benefits. As shown in Table 6-8, the estimated value of User Benefits ranges from $620 million in Alternative 1 to $1,244 million in Alternative 3. Because User Benefits include travel cost metrics, the FRA did not estimate travel cost savings separately for Regional rail. This equates to an average of $13 in User Benefits per regional rail trip (across the five regional markets of Washington, D.C./Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York/Connecticut, and Boston) under Alternative 1, to an average of $23 per regional rail trip for Alternative 3.

| Net of No Action Alternative, in millions of $2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Annual Estimated Value of User Benefits (Travel Time Savings) | $620 | $946 | $1,244 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

Across all nine Economic Development workshops conducted along the NEC corridor as part of the Economic Effect analysis, participants uniformly valued reliability of service as the most important service quality of service. Reliable service was viewed as a necessary condition for rail to be adopted by travelers and to spark economic development, without which travel time savings, additional frequencies and connectivity were not useful to the traveler-a faster unreliable train is not valued more than a slower unreliable train because travelers cannot plan and incur an opportunity cost. Although investments will be made to the corridor under the No Action Alternative, these investments will not be sufficient to return the corridor to a state of good repair. Thus, rail travel is projected to, at best, retain a similar level of reliability as is present in today's service. By contrast, all Action Alternatives offer reliable travel by design. Thus, while reliability is an outcome of the Action Alternatives relative to the No Action Alternative, it does not distinguish among the individual Action Alternatives-all are designed to provide reliable performance. While the increase in reliability for the Action Alternatives is indeed a benefit to users and operators, the metric is difficult to calculate with the level of available information at this stage of the planning process; thus, the FRA did not undertake further estimation of this outcome as part of the economic effects analysis.

The quantitative analysis focuses on the travel cost savings associated with Intercity rail only. Travel cost savings for Intercity rail include two components: 1) savings incurred by base Intercity-Corridor passengers who use the service in the No Action and Action Alternatives and experience lower fares in all Action Alternatives. (The base Intercity-Express riders do not incur travel cost savings since the fares do not change across alternatives.); and 2) savings incurred by passengers diverted from other modes of transport to Intercity passenger rail service. This includes savings incurred by passengers diverted from Intercity-Express rail service to Intercity-Corridor rail services in the Action Alternatives, due to the lower fares and increased frequency for the Intercity-Corridor service. The travel cost savings of diversions to Regional rail from other modes (primarily auto or bus for Regional services) accommodated by additional NEC capacity utilized by regional providers is included in the User Benefits estimation described in the Travel Time Savings section. The utility function used to estimate User Benefits considers travel times and costs; as a result, travel costs are not shown separately for Regional rail.

The FRA developed annual travel cost savings corresponding to the No Action Alternative as part of the Intercity travel demand modeling for 14 metropolitan areas. The travel cost savings take into account the net change in access/egress costs, fares or vehicle operating costs, and parking costs for trips diverted to Intercity rail from all other modes. Total potential cost impacts are calculated by multiplying the number of trips diverted from (by each mode) with by the difference in costs between the two modes for each zone pair, and then summed up to at the metropolitan statistical areas metropolitan area level. This analysis estimated costs in 2013 dollars and escalated to 2014 dollars using GDP Chained Price Index Deflators.

Table 6-9 shows the 2040 Intercity travel cost savings associated with Action Alternatives relative to the No Action Alternative in millions of 2014 dollars. The table summarizes the Intercity effects for the Action Alternatives for all four modes. The negative total for bus indicates that the diversion to passenger rail from bus would cost more to users than the No Action Alternative. However, all Action Alternatives result in travel cost savings overall, with Alternative 3.4 (Central Connecticut/Worcester) having the greatest savings of $1.98 billion. To put these values into context, Alternative 1 would save users enough travel costs to buy 95,000 new automobiles costing $20,000 each, or to buy 12.6 million train trips between Washington, D.C., and New York Penn Station at an average cost of $150.

| Trips | Net of No Action Alternative, in millions of $2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Air | $152 | $187 | $205-$215 |

| Auto | $592 | $668 | $686-$719 |

| Bus | ($48) | ($72) | ($95)-($88) |

| Rail | $1,204 | $1,147 | $1,061-$1,139 |

| TOTAL All Modes | $1,900 | $1,929 | $1,857-$1,985 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: Travel cost savings are reported for the Balanced Fare Scenario for each Action Alternative. The base Intercity-Express riders do not incur travel cost savings since the fares do not change across alternatives. Base Intercity-Corridor riders incur reduced the fares by 30 percent for all the Action Alternatives when compared to the No Action Alternative, and hence incur travel cost savings.

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

Additional passenger rail capacity provides an opportunity for commuters to divert from transportation modes such auto, bus, and air to Intercity and Regional rail service, and between rail services. This diversion has the potential to reduce the likelihood of being in a crash for those substituting their current mode of transportation for rail transportation. The avoidance of crashes prevents loss of life, protects quality of life and human capital, as well as property damage.

The analysis does not estimate the effects on safety for diversions from bus, rail, and air transportation because those modes of transportation will continue to provide service. Even if some travelers divert to Intercity and Regional rail from bus or auto, or to Intercity-Express from all other Intercity rail modes, the analysis assumes those services will continue to operate and contribute to crashes at the same rate. The travel market analysis conducted for this assessment is unable to predict if there would be a reduction in the number of routes or the frequency for these other modes if load factors were to fall below a certain criteria. As a result, changes to safety are estimated only for passengers who divert from auto to Intercity and Regional rail.

Passenger rail provides an alternative to using congested highway corridors and improves safety for travelers who divert from auto travel while increasing the accessibility for the region's populations to jobs, education, and recreational opportunities. Better access to rail would result in vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) saved with passenger rail users no longer using autos. This reduces the likelihood of crashes and associated deaths, injuries, and property damage as travelers use the new and expanded passenger rail services.

Table 6-10 shows the safety benefits for each Action Alternative for Intercity and Regional rail based on diverted auto VMT and the associated crash rates and value of crashes avoided.

| Net of No Action Alternative, in millions of $2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3 | |

| Auto Safety Costs Avoided: Intercity | $196 | $266 | $277-$303* |

| Auto Safety Costs Avoided: Regional | $223 | $278 | $400 |

| Auto Safety Costs Avoided: TOTAL | $420 | $543 | $677-$703* |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Note: Figures shown for all Action Alternatives include Intercity and Regional service. Totals may not add due to rounding. Figures for each of the Alternative 3 options include the total for Alternative 3 Regional service.

* Range of Alternative 3 route options

The FRA developed annual changes in criteria pollutants corresponding to the 2040 Action Alternatives as part of the air quality analysis, described in more detail in Chapter 7, Section 7.12. The air quality analysis estimated the potential annual impacts of each Action Alternative in comparison to the No Action Alternative, with respect to changes in tons of criteria pollutants associated with roadways (diverted VMT), diesel trains, and electric trains. The emissions consider Intercity, Regional, and freight rail services for an existing energy profile and a future energy profile.

Table 6-11 shows the total emissions effects in the region by Action Alternative. Positive values of emissions indicate the Action Alternative reduces emissions costs in the region; negative values of emissions indicate that the Action Alternative generates additional emissions costs in the region. As shown, all Action Alternatives result in emissions savings to the region compared to the No Action Alternative, assuming future, more efficient energy profiles (described in Chapter 7, Air Quality). Even with existing energy profiles, only Alternative 3.2 (Long Island/Providence) would generate negative values. Alternatives 1, 2, and 3.4 (Central Connecticut/Worcester) show the greatest environmental benefits under both energy profiles, but compared to other travel market effects, the emissions benefits are small.

| Net of No Action Alternative, in millions of $2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Existing Energy Profile | $22 | $20 | $6 |

| Future Energy Profile | $25 | $28 | $18 |

| Alternative 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Connecticut/ Providence (3.1) | Long Island/ Providence (3.2) | Long Island/ Worcester (3.3) | Central CT/ Worcester (3.4) | |

| Existing Energy Profile | $3 | ($1) | $2 | $21 |

| Future Energy Profile | $14 | $11 | $15 | $30 |

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

Although the NEC economies are concentrated in services, they retain a small goods production base, host some of the nation's largest marine ports requiring efficient landside access, and account for a large share of the U.S. consumer market. These are all factors that underscore the need for continued and efficient goods movement in the corridor for continued economic health. All three Action Alternatives would help ease select chokepoints in the corridor, offering benefits for freight movements as well as the passenger service. The Action Alternatives do not differ measurably in the freight-related economic outcomes that they offer. The Action Alternatives assume that current service levels for freight rail will be preserved along the NEC. This means that the volume of freight moved through the corridor would not differ under the No Action or Action Alternatives.

In addition to preserving current service levels for freight railroads, the FRA considered opportunities to accommodate the future growth and improvement of freight rail service within the Affected Environment. As noted in Chapter 5, Transportation, representative freight opportunities considered in the development and analysis of the Action Alternatives include the following:

The preservation of existing freight service levels combined with opportunities to add capacity at key locations along corridor is important for the health of freight-dependent industries in the corridor. For example, the Delmarva Peninsula hosts small manufacturers and a large agricultural industry that relies on regular shipments of grain. Moreover, many of the nation's Atlantic seaports are east of the corridor but serve markets along and west of the corridor. Maritime freight volumes are anticipated to grow between now and 2040. This is a result of growth in the U.S. population as well as changes in trade patterns driven by the expansion of the Panama Canal, the industry's shift to greater use of larger ships that require efficient loading/unloading and distribution capabilities, and economic growth among world trading partners. Ports' competitiveness and the region's ability to retain and attract freight-dependent industries are supported by the preservation of existing service levels and opportunities to add capacity at key locations.

This Travel Market section began with a discussion of how NEC capacity constraint acts as a brake on the region's economic potential. The following discussion quantifies the constraint and elaborates on other benefits associated with gaining capacity. The No Action Alternative is capacity constrained; that is, it cannot accommodate the full volume of passengers who want to travel by rail. As the travel market effects discussion and Table 6-5 and Table 6-7 in particular describe, there are tangible economic benefits when travelers are able to utilize rail to make their trips.

Alternative 2, and to a greater extent, Alternative 3, provide capacity that may permit physical redundancy at locations such as tunnels and other key junctures, fostering greater operational resilience, flexibility, and ability to recover from unexpected events.

Detailed more fully in Appendix B.I, Ridership Analysis Technical Memorandum, an analysis of peak-hour peak-direction rail demand at key screenlines along the corridor concluded that the tightest constraint in the corridor was at the Hudson River where 6,600 more passengers want to travel by rail per hour than can be accommodated under the No Action Alternative. Alternative 1 offers an improvement over the No Action Alternative, but remains constrained with demand for rail service exceeding available seats by roughly 2,900 passengers per hour. Alternatives 2 and 3 fully address the capacity constraints present in the No Action Alternative and accommodate projected demand. The ability to accommodate future demand also benefits current operations since Alternatives 2 and 3 (especially Alternative 3) provide sufficient capacity that may provide physical redundancy at key locations such as tunnels and elsewhere along the corridor, fostering greater operational resilience. The additional capacity allows for greater flexibility and faster recovery from unanticipated incidents, though the degree to which network resilience improves would depend on how the corridor would be operated.

This section describes the anticipated net revenue contributions associated with the O&M of the Action Alternatives for the horizon year of 2040, assuming full operations of the Action Alternatives. Â The Intercity services proposed in the Action Alternatives would offset increased annual O&M costs with a corresponding increase in passenger fare and food and beverage revenues. For all Action Alternatives, Intercity annual revenues would exceed annual O&M costs, which would generate excess revenues that could be used to pay for additional services or the capital investments required by the services. Tables 4-15 and 4-16 in Chapter 4, Alternatives Considered, present the O&M cost estimates for Intercity services only. In light of the individual railroad operator policies regarding fares and operating subsidies, the FRA did not estimate revenues for Regional services, and net revenue contributions are only estimated for Intercity service.

The FRA developed the O&M cost estimates for the Action Alternatives through an iterative process, balancing operating costs with ridership and revenues. This process included cycles of review and validation and determining how the changes in service and operations, resulting from an Action Alternative, would require adjustments to estimated future costs since some services would be different than what is operated today. The analysis demonstrated that each of the Action Alternatives are able to generate an operating surplus.

The analysis also demonstrated that the No Action Alternative is able to generate an operating surplus. However, the No Action Alternative did not undergo this iterative balancing process due to the expectation that its service plan will continue current service levels and fares on the NEC as a baseline. Fares per passenger are therefore higher in the No Action Alternative than in each of the Action Alternatives. The significant expansion in total intercity seats offered in the Action Alternatives allows an intercity operator to generate substantial revenue through higher passenger volumes at lower per-passenger costs. The No Action Alternative may also incur additional operating costs due to the higher risk of unplanned service disruptions resulting from infrastructure that is not in a state of good repair, or due to increased costs caused by operating in a highly constrained environment with many chokepoints that limit operational flexibility and the ability to recover from service issues.

The evolution of the travel market described in Section 6.3.4 above removes a burden on the region's economy, and allows travelers to make different travel choices-trading off time for cost in many cases. This section focuses on the qualitative attributes of the service that could influence the nature of the economic development opportunities that could occur as the market adapts the change in travel patterns. Businesses would adapt to capitalize on access to new and expanded labor markets. Travelers will be able to use rail more often and for a greater variety of trips than possible under the No Action Alternative. The economic development response may have a variety of dimensions that range from station area development (which is the most local) to labor market effects (which are typically regional) to agglomeration effects (which can vary in scale from a single metropolitan economy to an economically integrated urban megaregion).

In this analysis, changes in the travel market are applied to understand the potential nature of possible economic development outcomes. In order to understand this dynamic, FRA conducted a series of Economic Development Workshops with knowledgeable experts drawn from the academic, development, business and planning communities. The purpose of the Economic Development Workshops was to supplement the data-driven portion of the economic effects assessment with expert opinion on the probable market response to the new passenger rail services offered under these alternatives. The travel demand forecasting tools used by the FRA did not estimate the effects of potential local growth on ridership and revenue. The FRA used the insights from the Economic Development Workshops to qualitatively understand the potential for change in response to passenger rail improvements.

Information gathered from nine Economic Development Workshops held across the corridor in October 2014 helped in understanding the probable market response to the new passenger rail services offered under the Action Alternatives. Workshops helped inform an understanding of the following:

The workshops helped identify metrics used to measure agglomeration effects, labor market effects, and potential localized station area development.

The benefits of effective density accrue to workers as well by expanding their ability to access a wider range of offices, retail, entertainment centers, and other land uses within the same travel time. Residents' value of being able to access a variety of activity centers and land uses within the urban economy was at the heart of the "City Region User" concept described in the Economic Development Workshops completed as part of the Economic Effects assessment. The City Region User is a traveler with the ability to utilize a greater range of amenities within a single metropolitan region such as New York because of enhanced metro region mobility. Greater mobility allows the City Region User to expand his range of activities in the local economy-making the region more attractive for households and supporting local consumption and associated economic activity.

As noted earlier in this Chapter, transportation investment influences economic outcomes when and only if it first solves a transportation challenge. For this reason, the key findings of the Transportation Chapter (Chapter 5) and Ridership Analysis Technical Memorandum (Appendix B.6) are cited here for reference (Section 6.1, Impacts to Linked Trips).

In summary, the operation of the Action Alternatives provides travelers with reliable and more-frequent rail service, offers options for faster trips, and offers a greater variety of pricing options. As a result, the market share for Intercity rail grows relative to the No Action Alternative, rising from 4 percent of the rail market to 7 percent for each of the Action Alternatives.

| Passenger Rail Trips | In thousands of one-way trips unless otherwise labeled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing | No Action Alternative | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Alternative 3* | |

| Interregional | 14,700 | 19,300 | 33,700 | 37,100 | 39,000 |

| Regional | 324,500 | 419,800 | 474,500 | 495,400 | 545,500 |

| TOTAL Rail Trips | 339,200 | 439,100 | 508,200 | 532,500 | 584,500 |

| % Interregional | 4% | 4% | 7% | 7% | 7% |

| % Regional | 96% | 96% | 93% | 93% | 93% |

| Net Change Interregional Relative to Existing Interregional | - | 4,600 | 19,000 | 22,400 | 24,300 |

| Net Change Regional Relative to Existing Regional | - | 95,300 | 150,000 | 170,900 | 221,000 |

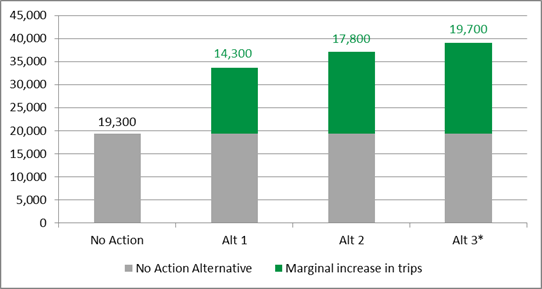

| Net Change Interregional Relative to 2040 No Action Alternative Interregional | - | - | 14,400 | 17,800 | 19,700 |

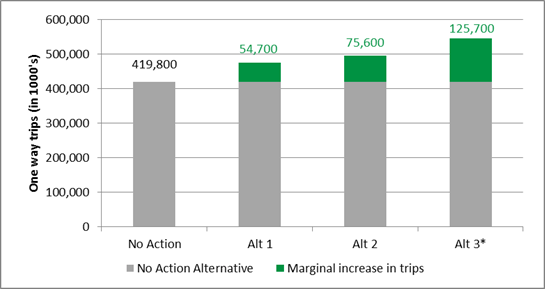

| Net Change Regional Relative to 2040 No Action Alternative Regional | - | - | 54,700 | 75,600 | 125,700 |

| Passenger Rail Trips | Central Connecticut/ Providence (3.1) |

Long Island/ Providence (3.2) |

Long Island/ Worcester (3.3) |

Central Connecticut/ Worcester (3.4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interregional | 38,900 | 38,700 | 39,800 | 38,600 |

| Regional | 545,500 | 545,500 | 545,500 | 545,500 |

| TOTAL Rail Trips | 584,400 | 584,200 | 585,300 | 584,100 |

| % Interregional | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% |

| % Regional | 93% | 93% | 93% | 93% |

| Net Change Interregional Relative to Existing Interregional | 24,200 | 24,000 | 25,100 | 23,900 |

| Net Change Regional Relative to Existing Regional | 221,000 | 221,000 | 221,000 | 221,000 |

| Net Change Interregional Relative to 2040 No Action Interregional | 19,600 | 19,400 | 20,500 | 19,300 |

| Net Change Regional Relative to 2040 No Action Regional | 125,700 | 125,700 | 125,700 | 125,700 |

Source: Derived from Table 32 of Section 6.1 of the Ridership Analysis Technical Memorandum (Appendix B.I)

* Average of Alternative 3 route options

Note: The FRA adjusted the NEC FUTURE Interregional Model based on issues identified during the Tier 1 Draft EIS comment period and a reassessment of the overall model outcomes. These adjustments did not affect the relative findings of the Action Alternatives (when compared to the No Action Alternative), but did result in modifications to the total numbers of trips and their distribution by station or metropolitan area. The Preferred Alternative Report (Volume 1, Appendix BB) contains a detailed description of the reasoning for these adjustments and the process used, and a summary of the changes in the model results, compared to the results presented in the Tier 1 Draft EIS.

Figure 6-2: 2040 Interregional Passenger Rail Trips

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

*Average of Alternative 3 route options

Note: The FRA adjusted the NEC FUTURE Interregional Model based on issues identified during the Tier 1 Draft EIS comment period and a reassessment of the overall model outcomes. These adjustments did not affect the relative findings of the Action Alternatives (when compared to the No Action Alternative), but did result in modifications to the total numbers of trips and their distribution by station or metropolitan area. The Preferred Alternative Report (Volume 1, Appendix BB) contains a detailed description of the reasoning for these adjustments and the process used, and a summary of the changes in the model results, compared to the results presented in the Tier Draft 1 EIS.

Figure 6-3: 2040 Regional Passenger Rail Trips

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

*Average of Alternative 3 route options

Note: For the Tier 1 Final EIS, the FRA adjusted the NEC FUTURE Interregional Model based on issues identified during the Tier 1 Draft EIS comment period and a reassessment of the overall model outcomes. These adjustments did not affect the relative findings of the Action Alternatives (when compared to the No Action Alternative), but did result in modifications to the total numbers of trips and their distribution by station or metropolitan area. The Preferred Alternative Report (Volume 1, Appendix BB) contains a detailed description of the reasoning for these adjustments and the process used, and a summary of the changes in the model results, compared to the results presented in the Tier 1 Draft EIS.

What this means is that the potential for labor market effects and the ability to move even larger numbers of workers efficiently in and out of the NEC's commercial centers is large, given the size of the market in absolute terms. However, the potential for agglomeration and economic "collaboration" among the metropolitan economies is enhanced by the increase in intercity travel-through the enhanced ability to share specialized labor, partner for research, or coordinate with multiple business units or contractors to compete in the larger market.

The FRA's ridership analyses confirm that New York dominates both the regional and interregional travel market across the Affected Environment. Approximately 75 percent of projected Regional rail trips are concentrated in the Northern New Jersey, New York, and Southwestern Connecticut geographic area. More than 80 percent of interregional rail trips have at least one trip end in the Northern New Jersey, New York, and Southwestern Connecticut geographic area. The balance of the linked trips (25 percent regional and less than 20 percent of interregional trips) is distributed across the balance of the corridor. This is borne out by the findings of the Economic Development Workshops conducted for the Economic Effects and Growth analysis. The participants at each workshop along the NEC selected New York as the most important market for greater rail service connectivity-even when other major markets were physically closer to them. New York City itself sought better mobility within its own economy; participants did not identify the need for greater rail capacity to connect to other major NEC markets except for areas surrounding New York that could supply labor. This suggests that the corridor will remain a New York-centric economy even as smaller individual markets become more integrated over time. Table 41 in Section 6.4 of the Ridership Analysis Technical Memorandum (Appendix B) compares projected demand to projected supply and finds the following:

These results demonstrate that the first and largest potential economic impact to the region is greater flow of people within the major metropolitan economies through the increased volume of commuter rail accommodated by the Action Alternatives relative to the No Action Alternative. Alternative 1 accommodates more than 54 million additional annual one-way trips in the corridor compared to the No Action Alternative. Alternative 2 accommodates an additional 20.9 million annual one-way trips more than what Alternative 1 provides. Alternative 3 provides even greater capacity, which based on the supply-demand analysis, exceeds what will be need before 2040-accommodating growth beyond that date.

The additional commuting capacity enables greater accessibility for workers and employers. Business productivity benefits from employers' access to a broader and more diverse labor market with a better fit of workers skills, and access to a wider customer market. Such accessibility improvements provide increased efficiency through reduced labor costs, improved communication, higher utilization of infrastructure and thus lower costs per user, and increased interaction with similar businesses. Collectively, accessibility and the associated efficiency that comes with businesses' ability to draw from a large labor pool support increases in the effective economic density (or clustering) of economic activities in those urban markets where the labor gains are achieved.

The second most important potential economic impact is the greater flow of people between the major commercial centers. As metropolitan economies grow in size and become more productive with gains in regional accessibility (described above) this, in turn, sparks greater demand for intercity travel since these larger markets have greater demand for trade and commerce with one another within the corridor. This demand is driven by the need for specialized services not available in their local economy, efforts to expand market share by establishing a presence in new markets, and efforts to take advantage of lower cost locations in proximity to the main business centers for those functions that do not benefit from being located in the corridor's largest urban economies.

By accommodating this intercity exchange of services-information and innovation through expanded opportunities for face-to-face contact-the greater provision of Regional rail allows the major economies along the corridor to grow larger and more productive than they would in the absence of such capacity. The Action Alternatives fully accommodate this demand. Though a small part of the overall travel market, the volume of Intercity trips more than doubles over what is experienced today. Alternative 2 nearly doubles what would be anticipated under the No Action Alternative. Alternative 3 adds excess capacity beyond what is projected to be needed before 2040. The reliability and mobility of the service improves the overall quality of life-both businesses and employees are attracted to the region-which supports additional growth and development.

Finally, the third potential economic impact is the development that occurs around stations as the real estate market capitalizes on the travel time savings enjoyed by rail travelers, and the increase in station use and ridership generated by access to more trains and locations. Economic development effects are some of the largest potential outcomes of the Action Alternatives; failure to consider them on some level would result in an incomplete analysis. Balanced against this need for information are the limitations of a quantitative modeling approach at this stage of planning. As a result, the analysis incorporated knowledgeable experts from the development, academic/non-profit, and planning professions to help identify what characteristics of the alternatives or the places created the greatest potential for economic development to occur in response to the rail investment. Based on this information, the FRA identified a series of metrics to measure those development potential factors. (Appendix D, Economic Development Workshop Summary describes this process in detail.) The FRA populated the metrics that were developed out of the workshops based on the description of the Action Alternatives and other study information and are presented in the following sections. These metrics provided as a barometer or leading indicators of economic development potential as a means to compare possible economic outcomes associated with the Action Alternatives.

Effects on Connecting Corridors

Although the primary focus of this analysis is along the physical rail corridor of the Action Alternatives, connecting corridors may also experience economic development effects in terms of station area development, labor market effects, and agglomeration economies. While all of the Action Alternatives assume the same level of connecting corridor service as available today-that is, no capital or operating investment in the connecting corridors-once a connecting train reaches the NEC, it benefits from the investments made under the Action Alternative for the balance of the trip.

For example, consider a passenger traveling from Harrisburg, PA, to New York City. The trip from Harrisburg to Philadelphia takes 1 hour 40 minutes. The trip from Philadelphia to New York City takes 1 hour 11 minutes by Intercity-Express, excluding wait time between trains. The trip from Harrisburg to New York City in total would take 2 hours 50 minutes without any wait time, or roughly 3 hours 30 minutes, assuming a 40-minute wait time12 in Philadelphia to transfer. Some of the Action Alternatives are designed with a pulse-hub style system with regular, scheduled, cross-platform transfers for this style of trip. This time estimate excludes the time that it takes for the traveler to get to the station from home. This makes the train a reasonable option for a day trip for business for Harrisburg travelers, but not one with a measurable advantage over auto travel. Drive time from Harrisburg to New York City is estimated at about 3 hours, in the absence of congestion delays. While parking in New York City may be challenging, travelers have the advantage of starting the trip directly from their residence.

More connections in Philadelphia and faster service to New York City offer the potential to change this trade-off in rail's favor. For example, Alternative 3.1 (Central Connecticut/Providence) would reduce the Philadelphia to New York City time to about 40 minutes for a total rail travel time of 2 hours 20 minutes, exclusive of wait time. Alternatively, for those travelers not taking the Intercity-Express train, the trip from Philadelphia to New York City would be about 1 hour 15 minutes for a total travel time of about 2 hours 30 minutes exclusive of wait time. Assuming more-frequent service and well-timed transfers between trains in Philadelphia and Harrisburg, travelers could access New York City by rail in less than 3 hours, making rail more competitive with an auto trip, and roughly the time of an Acela trip between Washington, D.C., and New York City today.

This offers the potential for station area development in Harrisburg as well as potential agglomeration economies as the effective distance between Harrisburg and New York City is reduced.

Development around station access points is among the most visible market change. It is also the most local in terms of geographic scale. The scale and character of the development is influenced by the nature of the rail service provided, as well as the ability of the surrounding area to plan for and provide the other necessary factors to support development around stations. Connecting infrastructure, available parcels of sufficient size to accommodate the new developments, and appropriate zoning are all examples of these necessary and complementary elements of station area development.

Furthermore, in considering economic effects of the three Action Alternatives, one of the largest questions is whether the cumulative changes in travel times and patterns of connectivity may change the way the individual metropolitan economies relate to one another as well. For example, do the changes in market access reinforce the dominance of the New York market, or by contrast, do the smaller cities realize greater benefit and close some of the gap with New York City? The FRA considered the potential for agglomeration in this analysis.

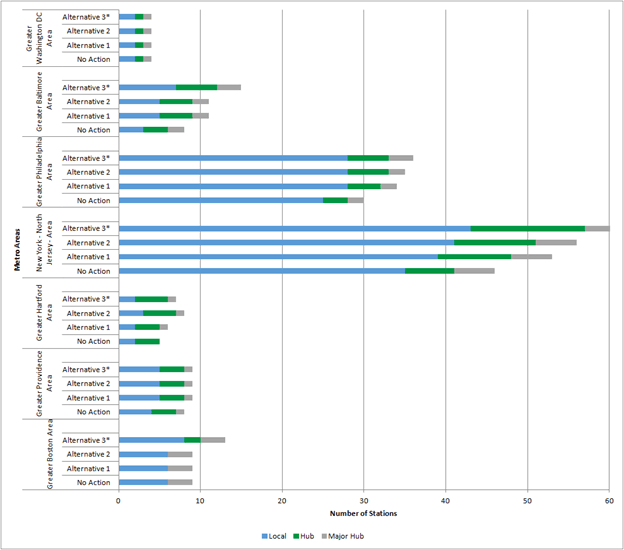

Station Area Connectivity

Figure 6-4 summarizes the differences in the number of Local, Hub, and Major Hub stations by alternative and location. As stations move along the spectrum from Local station to Major Hub, they increase the number of modal options and rail services clustered at their locations: The greater the number of connections, the greater the potential for station area development. Across the Action Alternatives, the Greater New York-North Jersey, Greater Philadelphia, and Greater Baltimore markets have the greatest gains in stations. Moreover, each gains one or more hub stations, which are focal points for development in the surrounding area. In several workshops, participants noted the economic development value of clustering modes in one place; hubs support greater development intensity than stations with just rail service. By contrast, the change in number and type of station in the Greater Washington, D.C., Greater Hartford, Greater Providence, and Greater Boston (except for Alternative 3) are modest at best.

Figure 6-4: Number of Stations of Each Category in the NEC FUTURE Station Typology

Source: NEC FUTURE team, 2015

Click to view larger version of Figure 6-4

Station Area Planning